|

Author(s)

Arne Langøen

Sandra Lawton

|

Contents

|

|

Published:

November 2009

Last updated: November 2009 Revision: 1.0 |

Keywords: vulnerable skin; periwound skin; venous leg ulcers; pressure ulcers; diabetic foot ulcers; venous eczema; contact dermatitis; allergens.

All periwound skin can become vulnerable and requires careful assessment and management.

Certain wound types cause dermatological problems in the surrounding skin and require particular care, including venous leg ulcers, pressure ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers.

Allergic reactions to substances used in wound management and skin care, such as cosmetics and soaps, may exacerbate periwound skin problems.

This short paper forms the third in a series of three articles examining care of the skin surrounding wounds. The first two papers examined the pathophysiology of vulnerable skin and the assessment and management required when caring for patients with wounds. The focus of this article is on those dermatological conditions that are directly related to specific wound types.

As discussed in papers one and two of this series, care of the periwound skin, including its protection against mechanical injury (such as tissue trauma caused by the removal of adhesive tapes and dressings) and chemical injury (caused by products used on the skin, bodily fluids and wound exudate), is an essential requirement for those providing wound and dermatological care [1] [2].

This paper examines dermatological problems associated with specific wound types, including venous leg ulcers, pressure ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers. In some cases, especially in leg ulcer management, vulnerable periwound skin can be the most challenging aspect of care and cause far more problems for the patient and carer than the wound itself.

Skin assessment involves obtaining a detailed dermatological history by questioning the patient, observing the skin meticulously and making detailed notes. This may provide clues to diagnosis, management and nursing care of the existing or potential problem [2] [3].

Periwound skin care is perhaps most challenging in patients with venous leg ulcers. A number of physiological changes in the skin are caused by changes in the venous circulation in such patients. Venous hypertension leads to micro-oedema, where red blood cells and other macromolecules leak into the extravascular space. There is release of iron pigment from haemoglobin, which results in brown staining of the skin (haemosiderin).

Patients with chronic venous ulcers often have lipodermatosclerosis, atrophie blanche, hyperpigmentation, dry, scaling and atrophic skin and venous stasis eczema. These conditions are often associated with vulnerable periwound skin that is thin and easily damaged by adhesives, for example. This skin condition can be further complicated by allergic or irritant reactions (see Tables 1 and 2 [4] [5]).

The key to successful management is to treat the chronic venous hypertension, either surgically or with compression therapy. Without this, local treatment will be ineffective.

|

Allergen |

Possible sources of allergen |

|

Rubber |

Gloves, bandages, hosiery |

|

Topical antibiotics |

Creams, ointments and medicated dressings |

|

Emulsifiers |

Stiffening agent in creams |

|

Perfumes |

Creams and bath additives |

|

Preservatives |

Creams and gels |

|

Adhesives |

Dressings and plasters |

|

Common allergens and their sources |

|

Adapted from Bourke J, Coulson I, English J. Guidelines for the management of contact dermatitis: an update. Br J Dermatology 2009; 18: 946-54, with kind permission of the publishers, Wiley-Blackwell.

Venous eczema can benefit from treatment with topical corticosteroids, although these must be used with caution as they can damage the thin and vulnerable skin if used incorrectly and may even exacerbate the condition. If the eczema is wet a topical corticosteroid cream is preferable; if the eczema is dry an ointment should be used. In severe cases, problems can be dealt with using potassium permanganate 0.01-0.03%, applied once or twice a week for two weeks or so, preferably in conjunction with corticosteroid therapy [6]. This will reduce the number of bacteria and reduce the secretion from both the wound and the eczema. Topical corticosteroids are generally used once or twice daily over short periods of one to two weeks and then stopped. However, in the case of gravitational eczema or allergic contact dermatitis surrounding a leg ulcer, the ulcer will usually be undergoing treatment by compression therapy and dressing changes will not allow this frequency of application. Occlusion enhances the potency of topical corticosteroids by aiding absorption and this should be considered when choosing a preparation [7].

Side-effects from the use of topical corticosteroids can include topical effects (thinning of the skin, irreversible loss of elasticity, striae, worsening of skin infections or acne) and systemic effects (pituitary and adrenal suppression, and Cushing's syndrome) and are related to potency, While it is important to use the least potent topical corticosteroid whenever possible, the treatment does need to be effective and using a more potent preparation initially may result in less topical corticosteroid being used in the long term [7]. When using topical corticosteroids their use and therapeutic effect should be monitored and evaluated. If there is a poor response to treatment the skin should be reassessed and differential diagnoses considered such as an infection (bacterial or fungal), or allergic contact dermatitis (possibly caused by a product used on the wound or skin, see Table 1). A recent study showed that 82.5% of patients with chronic leg ulcers had at least one positive patch test reaction [8].

Patients with venous leg ulcers are at risk of bacterial infections in the skin surrounding the wound, a condition often called cellulitis. It can be difficult to distinguish between cellulitis and venous eczema, since both conditions leads to oedema and erythema. They can also occur simultaneously [9]. Cellulitis is often associated with well-demarcated erythema, warmth, pain and tenderness to the touch, while dermatitis has more diffuse edges and more dry and scaling skin.

To reduce the risk of allergic reactions, Romanelli and Romanelli (2007) suggest the prophylactic use of an ointment comprising 50% soft white paraffin and 50% liquid paraffin [10]. It is important to recognise that the use of ointments can lead to folliculitis caused by blockage of the hair follicles, and therefore all emollient preparations should be applied smoothly in the direction of hair growth [11].

A film containing acrylate can be used as protection against wound fluid and fluid from eczema [11] [12]. The film protects for 72 hours, and should not be used in combination with local corticosteroid treatment, as the film will inhibit its effect. Zinc oxide can be used to protect the periwound skin; however, the salts in zinc inhibit the action of silver in the wound and thus zinc oxide should not be used in combination with silver dressings [11].

Showering or bathing should be encouraged where possible, and can be beneficial for both the wound and periwound skin problems. Using conventional soap products containing surfacants can have a drying effect on the skin, causing immediate after-wash tightness, dryness, redness, irritation and itch, and may damage the skin barrier [13] [14]. Emollient wash products should therefore be used.

When choosing a bandage or dressing for a patient with venous eczema, several factors should be taken into account, including the risk of allergic and toxic reactions, the severity of eczema, and the amount of fluid produced by both the wound and the eczema. A dressing with high absorbing capacity, no adhesive border and an inner layer with a low risk of producing toxic and allergic reactions should be preferred, such as those with an inner layer of soft silicone [15].

In many cases of superficial pressure damage such as stage 1 and 2 pressure ulcers, the damage has occurred because the peripheral circulation has been compromised. When the pressure on the area is relieved, the area is reperfused. The combination of obstruction or reduction of the circulation followed by reperfusion, leads to increased amounts of reactive oxygen species, which cause inflammation in the tissue [16] [17]. The inflammation, together with reduced circulation, makes the periwound skin more vulnerable.

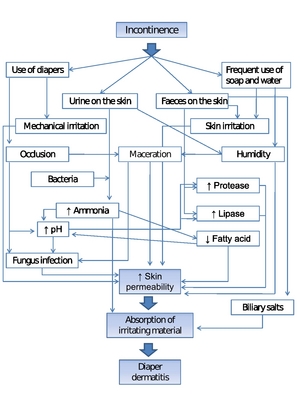

In stage 1 and 2 pressure ulcers, in addition to mandatory measures such as pressure relief, the skin may be protected with an ointment containing 50% soft white paraffin and 50% liquid paraffin or an acrylate-containing film to reduce the risk of skin breakdown. These wounds are often located in areas where contamination with urine and faeces is likely, which can cause a contact dermatitis rash (see Figure 1) [18] and therefore a barrier cream or ointment can help to protect the skin.

Stage 3 and 4 pressure ulcer damage involves deeper layers of the skin and structures under the skin. In some cases there are undermined areas with deep cavities and fistulae. Therefore the periwound area is at risk from excoriation from wound exudate or discharge from the fistulae.

When applied carefully to the affected area, barrier ointments can protect periwound skin from the effects of humidity, sweat, protease and lipase production from the wound, urine and faeces and friction from bed linen [19]. In cases where the skin is at greater risk, a good alternative is to protect the periwound skin with either a hydrocolloid or a polyurethane film. However, frequent removal of the hydrocolloid paste or polyurethane film dressings can lead to damage of the periwound skin, owing to a stripping effect. Selecting an appropriate dressing that allows effective exudate management will help to protect the surrounding skin from damage. It is important that these measures are taken alongside the removal of causative factors and the instigation of effective pressure relief.

Adapted from: Langøen A, Vik H, Nyfors A. Diaper dermatitis. Classification, occurrence, causes, prevention and treatment. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1993; 113(14): 1712-5 with kind permission of the publisher.

Diabetic neuropathy causes both dry and scaling skin and an increased production of callus in the periwound area. Diabetic patients can also have ischaemia because of microangiopathy, resulting in dry, atrophic, cold skin on which hair fails to grow [20].

The dry skin of the diabetic foot should be treated with emollient products. Emollients are an important group of agents that play an integral part in the treatment and maintenance therapy of all dry, scaling skin disorders. Emollients come in a variety of formulations and are used for washing, bathing and moisturising.

To treat hyperkeratosis, areas of callus should be removed regularly by a podiatrist. Healthcare professionals should strongly encourage patients to prioritise this treatment.

Both adhesive and non-adhesive dressings can be used in patients with hyperkeratosis, but it is commonly accepted that dressings with limited absorbing capacity, such as hydrocolloids, should be avoided.

This paper describes the common dermatological problems associated with the periwound skin of specific wound types. The key to good management in all cases is gaining an accurate diagnosis and understanding of the cause of the problem and knowing when to refer to a specialist. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge the impact that dermatological disease will have on the patient's quality of life and the wound healing rate. It is easy to misdiagnose even common skin conditions and inappropriate treatment is often the cause of an exacerbation of the condition and great distress to the patient.

1. Flour M. Pathophysiology of vulnerable skin. World Wide Wounds 2009; available from URL: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2009/September/Flour/vulnerable-skin-1.html.

2. Lawton S, Langøen A. Assessing and managing vulnerable periwound skin. World Wide Wounds 2009; available from URL: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2009/October/Lawton-Langoen/vulnerable-skin-2.html.

3. Lawton S. Assessing the patient with a skin condition. Practice Nurse 2005; 30(5): 43-8.

4. Bourke J, Coulson I, English J. Guidelines for the management of contact dermatitis: an update. Br J Dermatol 2009; 160(5): 946-54.

5. Lawton S, Gill M. Contact dermatitis: types, triggers and treatment strategies. Nurs Standard 23(34): 40-6.

6. Dealey. The Care of Wounds: A guide for nurses. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

7. Radley K, Shaw E. Topical corticosteroids and their use in venous leg ulcers. Dermatological Nurs 2007; 6(2): 10-15.

8. Barbaud A, Collet E, Le Coz CJ, Meaume S, Gillois P. Contact allergy in chronic leg ulcers: results of a multicentre study carried out in 423 patients and proposal for an updated series of patch tests. Contact Dermatitis 2009; 60(5): 279-87.

9. Fowler E, Carson S. Understanding peripheral edema and managing the edematous lower leg. In: Krasner DL, Rodehaver GT, Sibbald RG, editors. Chronic Wound Care: A clinical source book for healthcare professionals. Fourth edition. Malvern: HMP Communication, 2007.

10. Romanelli M, Romanelli P. Dermatological aspects of leg ulcers. In: Morison MJ, Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, editors. Leg Ulcers. A problem-based learning approach. London: Mosby Elsevier, 2007.

11. Sibbald RG, Cameron J, Alavi A. Dermatological aspects of wound care. In: Krasner DL, Rodehaver GT, Sibbald RG, editors. Chronic Wound Care: A clinical source book for healthcare professionals. Fourth edition. Malvern: HMP Communication, 2007.

12. Hampton S, Stephen-Haynes J. Skin maceration: assessment, prevention and treatment. In: White R, editor. Skin Care in Wound Management: Assessment, prevention and treatment. Aberdeen: Wounds UK, 2008.

13. Ananthapadmanabhan KP, Moore DJ, Subramanyan K, Misra M, Meyer F. Cleansing without compromise: the impact of cleansers on the skin barrier and the technology of mild cleansing. Dermatol Ther 2004; 17(Suppl 1): 16-25.

14. Subramanyan K. Role of mild cleansing in the management of patient skin. Dermatol Ther 2004; 17(Suppl 1): 26-34.

15. Thomas S. The role of dressings in the treatment of moisture-related skin damage. World Wide Wounds 2008; available from URL: http://www.worldwidewounds.com/2008/march/Thomas/Maceration-and-the-role-of-dressings.html.

16. Collier M, Moore Z. Etiology and risk factors. In: Romanelli M, Clark M, Cherry G, Colin D, Defloor T, editors. Science and Practice of Pressure Ulcer Management. London: European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel/Springer, 2006.

17. Coleridge Smith PD. Oxygen, oxygen-free radicals and reperfusion injury. In: Krasner DL, Rodehaver GT, Sibbald RG, editors. Chronic Wound Care: A clinical source book for healthcare professionals. Fourth edition. Malvern: HMP Communication, 2007.

18. Langøen A, Vik H, Nyfors A. [Diaper dermatitis. Classification, occurrence, causes, prevention and treatment]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1993; 113(14): 1712-5.

19. Bale S, Cameron J, Meaume S. Skin care. In: Romanelli M, Clark M, Cherry G, Colin D, Defloor T, editors. Science and Practice of Pressure Ulcer Management. London: European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel/Springer, 2006.

20. McIntosh C, Newton V. Superficial diabetic foot ulcers. In: White R, editor. Skin Care in Wound Management: Assessment, prevention and treatment. Aberdeen: Wounds UK, 2008.