|

Author(s)

Glen Cousquer

|

Contents

|

|

Published:

Last updated: January 2010 Revision: 1.0 |

Mountain Guides, Instructors and Leaders will often find themselves using and relying on pack animals, such as mules, on expedition. In the absence of motorised transport, the mule’s ability to carry heavy loads over difficult mountainous terrain is thus exploited.

Many of these mules may start the expedition with wounds or develop wounds during the course of the expedition. Saddle sores, tethering wounds and bitting injuries are sadly commonplace and can have a significant impact on an animal’s welfare. The expedition leader is responsible for the health and welfare of all members of his team, including pack animals, and will need to manage any issue(s) that may jeopardise the success of the expedition. What does this mean in practice?

This case study will recount the experiences of a veterinary surgeon and Mountain Leader during a five day expedition through the Massif du Siroua, in the High Atlas of Morocco. The aetiology, prevention and management of saddle, harness and tethering sores will then be discussed in detail.

In this case study, the actions of each team member are inextricably linked to their socio-cultural, professional and educational backgrounds. A short account of these backgrounds will therefore be provided. The languages and methods used by the team members to discuss issues of wound management will also be described as these may have an impact on the degree of understanding achieved.

In April 2010, the author set out with a Moroccan Accompagnateur de Montagne (Mountain Leader) and a friend for a five day expedition through the Massif du Siroua. The four person team was completed by a local muleteer and his eighteen year old mule.

The Moroccan Accompagnateur and the author had known each other for two years but this was the first time they had worked together.

The Accompagnateur is in his mid forties and has spent most of his working life working as a mountain leader and, before that, a muleteer. Like the majority of people of his generation he received no formal schooling. He is from a traditional Berber family and is a devout Muslim. He speaks Berber, Arabic, French and a little English, allowing him to communicate relatively freely with the author and the muleteer.

The author is a veterinary surgeon, mountain leader and outdoor educator. He is in his mid thirties and has spent much of his working life working as a veterinary surgeon. He has been a keen mountaineer and horse rider for over twenty years. He speaks French and English fluently, allowing him to communicate relatively freely with the Accompagnateur.

The muleteer lives and grew up in a remote Berber village, of some 350 inhabitants, in the Massif du Siroua. The villagers are pastoralists and move their sheep, goats and other livestock from one grazing site to another. He is in his mid twenties and has spent most of his working life working as a muleteer or undertaking work within his local community. He has received some schooling although does not speak any languages other than Berber and Arabic.

On the eve of departure, the author asked to see the muleteer’s mule and its equipment. An examination of the mule was conducted and an evaluation made of the mule’s burdâa (straw stuffed saddle blanket) and bridle.

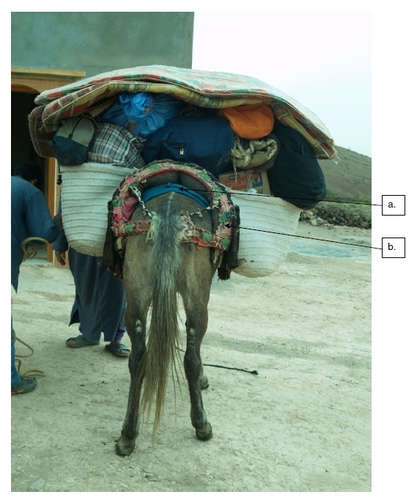

The mule was found to be in good bodily condition (condition score 3/5). No bitting injuries were identified. The mule did, however, show tendon sheath effusions in both its forelimbs and a tethering injury to its left pastern. The mule was not obviously lame at the walk but palpation of the digital flexor tendons and the pastern on the left fore elicited a brisk withdrawal response suggesting that the mule was in discomfort. An abrasion was identified over the mule’s left upper hind limb, caudal and distal to the tuber coxae (Figure 1). This abrasion was healthy and granulating well. The mule showed no pain response when palpating the dorsal midline and, significantly, no lesions were identified here.

a. Superficial sore distal and caudal to the tuber coxae.

b. Boney prominence of the tuber coxae.

c. Depression in the burdâa’s stuffing to accommodate the tuber coxae.

Examination of the burdâa showed a number of worn areas on the caudal inner surface of the blanket (Figure 2). The loss of material on the left side was particularly pronounced and would have allowed the exposed straw to contact the overlying skin. The padding of the burdâa at this point was clearly excessive: the tubular pad (e, d) becomes particularly prominent at point (f), creating an area of friction and increased wear.

c. Depression in the burdâa’s stuffing to accommodate the tuber coxae.

d. Actual position of the tuber coxae and resulting area of wear.

e. Straw filled tubular pad running the length of the burdâa.

f. Raised area at the caudal end of the pad.

The depression in the burdâa designed to accommodate the tuber coxae was situated too high and therefore failed to provide any such protection, resulting in the wearing of the material at point d (Figure 2). It was clear from this that the burdâa had never been personalised to fit the mule.

The traditional bit (Figure 3) was of poor quality and included a number of pieces of twisted wire. It did not appear, however, to have provoked any damage to the oral tissues, lips or commissures (Figure 4).

The author and the guide demonstrated to the owner the correlation between the sores and the poor fit of the burdâa. The muleteer appeared to be aware of the wounds to the pastern and thought they were connected to the tendon sheath effusions. The muleteer was given a set of cotton hobbles to use for tethering the mule. Their use was demonstrated. Finally, the mule was given a dose of ivermectin in order to treat any internal parasites.

An early departure on day 1 was necessary to avoid the heat of the day. The mule was loaded with all the group equipment (Figure 5). Both the author and the Accompagnateur expressed concern that the load was excessive. The muleteer, however, was adamant that his mule could cope with this sort of load. The load was secured with a long piece of rope that was passed across the mule’s ventral midline. Care was taken to position the rope across a small piece of material (Figure 6) that protected the animal’s girth.

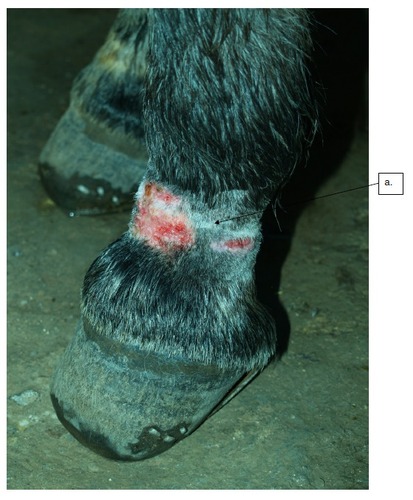

A distance of some 20km was covered that day. At the end of the day, the author requested that the mule be brought for re-examination. The mule’s left pastern wound was examined in the light and permission was obtained to clean and dress it.

The hair around the wound was trimmed back with curved scissors and the wound gently cleaned with a 4% Chlorhexidine solution diluted with water. Removal of the hair, dust, exudate and wound discharge allowed a more detailed evaluation of the wound to be made (Figures 7-8). The extent of the wound was shown to the muleteer who, it was found, thought the wound had been caused by stones. The circumferential nature of the wound, wrapping round the mule’s pastern was highlighted and the muleteer was shown how a nylon rope on his own wrist would easily produce friction burns and eventually an open sore.

The caudal aspect of the wound was particularly deep and contained an area of devitalised tissue. The wound was liberally lavaged and a dressing applied. The dressing chosen was a long strip of Duoderm Extra Thin (Convatec) from the author’s first aid kit. This was applied circumferentially around the pastern and secured in place with Micropore tape (3M). The area was then protected with a tubular bandage.

The dressing was left in place for three days. During this time, the muleteer was encouraged to use the cotton hobbles. Initially, this suggestion met with reticence as he was reluctant to trust in something new that his mule might be able to escape from. By the end of the second day, however, the hobble was being used as part of a tethering system: one end was fastened to the mule’s right pastern, the other end to the nylon rope (Figure 9). A prototype leather adjustable “bracelet” was also trialled during this time. This had been made from double thickness goat leather, measuring 3cm in width and stitched over two pieces of cord. The size of the bracelet was adjustable using a small leather loop. After measuring the pastern circumference at 23cm, a hole was placed to allow the leather loop to be blocked using a carved wooden olive.

Upon removal of the dressing on the evening of day 4, the tissues were found to look a lot less angry (Figure 10). The caudal aspect of the pastern wound still had a plug of devitalised tissue (Figure 11). The plug of tissue was removed by dissection and the wound liberally lavaged with spring water before applying a second dressing. On this occasion, the dressing used was Tiele (Johnson and Johnson). This was placed circumferentially around the pastern and secured in place with Micropore tape (3M). The dressing was then protected with a few layers of cohesive bandaging (Vetrap, 3M). The muleteer expressed his displeasure at this second wound dressing as he was due to pass through his home village the next morning. The importance of keeping the wound clean in order to promote healing was strongly emphasised.

The following day, the group arrived in the muleteer’s home village. The muleteer arrived in advance and, by the time the group had caught up with him, there was no sign of the dressing. It transpired that the muleteer had not wanted his friends and family to see his mule arrive with a dressing on its lower leg and had removed it. He explained his actions: claiming that he did not want people to think his mule was broken (“cassé”). The author made it known to the muleteer that this was not acceptable behaviour as the work undertaken to clean and protect the wound had all been undone. There remained a further afternoon’s walking and the expedition was not therefore over. The resulting situation was both disappointing and distasteful. The Accompagnateur sought to explain that the people in that village were “pas gentil”, that is too say “not nice”!

At the end of the afternoon, an afternoon in which the mule walked for two hours through the dust of the hammada, the muleteer was paid off. The author asked the Accompagnateur to emphasise to the muleteer the need to wash the wound liberally and regularly with water. The muleteer was given the leather “bracelet” but was not given the customary tip.

This case study highlights the various practical issues encountered when attempting to manage the saddle and tethering sores of a pack mule on expedition. These issues extend beyond the simple question of how best to manage the wounds for their management must take into account the underlying aetiology of the wounds and pay due attention to the respective rights and responsibilities of the various moral agents who bear a responsibility towards the mule. The wound cannot therefore be treated in isolation.

In mountainous terrain, the mule is widely recognised as the pack animal par excellence [1][2][3][4]. Milhaud and Coll [5] pay tribute to the mule, describing it as a precious auxiliary of the French Army that accompanied soldiers wherever the terrain and climate became too challenging. Today, the mule’s ability to support expeditions through tough mountainous country has seen it return to military service [6] in the mountains of Afghanistan, whilst its value as a pack animal continues to be recognised by trekking groups operating in mountain ranges throughout the world, including the High Atlas of Morocco.

The remote nature of the High Atlas, the absence of supplies, lack of facilities and distance from roadheads, mean that local people remain heavily reliant on pack animals, and particularly the mule, to transport fodder, building supplies, goods and other materials. An extensive network of mule trails crisscross the High Atlas, linking villages and remote mountain valleys. Pilgrimages to holy shrines, or marabouts, such as that of Sidi Chamarouch (2340m), on the Toubkal, are also typically undertaken by mule. It is this tradition, together with the system of mule trails that have evolved to support it, that has been exploited by the developing trekking industry. Today, the vast majority of trekking expeditions into the High Atlas make use of mules to transport equipment and supplies.

In practice, the guide’s and muleteer’s responsibilities to the mule overlap, making it difficult to say where the one’s start and the other’s stop. The guide is, however, the team leader for the expedition; his immediate duty is to ensure the success of the common project, namely the expedition, and his virtuous conduct will ensure that the goods internal to the expedition are realised. Failure to pay attention to the health and welfare of the mules clearly has the potential to jeopardise the success of the project and, indeed, future projects, in much the same way as failure to look after his own health or that of other group members [7]. The mountain professional’s responsibilities towards members of his group are widely understood to encompass the prevention and treatment of injuries and diseases where and whenever they arise; this is why so many outdoor qualifications require a valid First Aid certificate. Where mules are members of the expedition team, it can therefore be argued that the guide should be similarly prepared to prevent and treat any injuries or disease sustained by them during the course of the expedition.

The guide and, indeed, the tourist / trekker / tour agency are able to stipulate minimal standards of care and work. If it is accepted that working practices should not result in injury to the pack mule, certain practices such as the use of ill fitting, worn saddles or nylon ropes become unacceptable.

In meeting his responsibilities to the mule, the guide can consider the following questions:

Is the mule fit to work?

Is the mule’s burdâa fit for purpose?

Is the mule’s equipment fit for purpose?

Is the mule likely to be overloaded?

Does the mule require any treatment?

The guide, in his role as expedition leader, can decide that a mule is unfit for work and should not leave on expedition. In this case study, the mule was examined and found to be in reasonable condition. The mule was not obviously lame or otherwise debilitated. The wounds that were identified were unlikely to prevent the mule from completing the expedition. As such there were probably no grounds for declaring the mule unfit for work. It might be possible to insist that any mule leaving on expedition be free of wounds. Such a policy is likely to prove difficult to implement, however, particularly where replacement mules are hard to find or are in a similar condition. A policy whereby, a reserve mule is always included in the team can provide a valuable safety margin and should always be considered where the availability of replacement mules is doubtful.

The burdâa is a straw filled padded saddle blanket; whose principle purpose is to protect the back and distribute the load evenly over the weight bearing areas of a mule [1][8][6]. The weight bearing surface of a pack mule corresponds with the ribcage to either side of the midline. The vertebral column itself should not bear any weight if it is to be protected from pressure sores. The back of this mule was remarkably free of sores and this correlated well with the wide central gusset of the burdâa. Deficiencies in the fit of this burdâa were nevertheless identified and the muleteer was clearly aware that his mule had a sore. On the eve of departure, there was, however, no time to get the burdâa repaired and personalised; it was not therefore possible to eliminate these areas of increased pressure and friction.

The Expedition Leader can choose to declare a mule and its burdâa unfit for work if the latter is inadequately personalised to the mule’s back or in a poor state of repair, especially if the mule’s back is likely to suffer injury as a result. When resorting to this ultimate sanction, the Guide will need to arrange a replacement muleteer and mule. This may be difficult, or even impractical, making the imposition of this sanction difficult.

Repairs could be insisted on but, in practice, the muleteer may not always have the skills, knowledge or equipment to make the necessary repairs. Repairs will often then have to wait until the next souk day, when the muleteer can take the burdâa for repair.

The mule’s tethering injuries reflected the widespread use of nylon and plastic ropes to tether livestock throughout the High Atlas (Figure 12). These ropes are usually of narrow diameter, frayed, heavily contaminated and tied tightly around the mule’s pastern. As such they exert considerable force over a small surface area. They often produce friction burns and can even deposit fragments of nylon within the subcutaneous tissues. The use of wider, better designed tethering systems made from sacking, cloth or leather is to be encouraged [9]. The Society for the Protection of Animals Abroad (SPANA) promote the use of cotton hobbles (Figure 13). The construction of these hobbles increases the surface area over which pressure is applied and prevents the tether from over tightening around the pastern. Cotton is less likely to produce friction burns than nylon rope but is less resistant, requiring it to be replaced on a regular basis.

In this case study, it would, on reflection, have been sensible to stipulate more clearly that the tethering system be changed at the outset. The muleteer’s established routine and “way of doing things” did appear open to suggestion and change. Little resistance was identified, for example, to the administration of a dose of 250ml of sunflower oil with the mule’s evening ration of barley. It is likely, however, that this reflected the muleteer’s willingness to humour his employers rather than any new found awareness of the value of an energy dense food source to a hard working equine with little time to graze and adequately satisfy its energy requirements. After twice seeing the mule tethered with the nylon rope on days one and two, the muleteer was finally persuaded to accept the use of the cotton hobble. This wide loop of cord is closed around a fixed knot (Figure 13) and cannot therefore over tighten.

In the author’s opinion, the cotton hobble possesses a number of advantages over the nylon rope that is in widespread use throughout the High Atlas of Morocco. The muleteer, however, was more concerned about preventing the mule from straying. There are many systems in use that allow a pack animal to graze relatively freely without there being any risk of it running off and without the risk of injury. The range of techniques and systems used around the world by horsemen to secure their animals at a bivouac site are reviewed by Brager [8].

The Mountain Guide or Expedition Leader, as well as tourists and trekking companies could insist that a non-traumatic tethering system be used on all expedition pack mules. This requires the ready availability of an alternative substitute tether, such as the cotton hobble.

Hadrill [10] suggests that a pack animal can safely carry a third to a half of its own weight for several hours if it is in reasonable condition. This equates to some 40kg of load per 100kg of its body weight, or 120kg for a 300kg mule. It should be noted that this weight should be reduced to take into account the long days and steep terrain typically encountered in the High Atlas. The load carried by pack mules working in the High Atlas should not exceed 80kg [11]. In practice, this weight limit is often exceeded: Where the trekking group is small (1-4 people), the group equipment will be shared out amongst a smaller number of mules, resulting in overloading.

The Accompagnateur in this particular case was concerned that the mule might be overloaded and was ready to pay for an additional mule. For some reason, the decision not to take an additional mule and spread the load was made by the muleteer. Had the total load been quantified precisely, it might have been possible to stipulate a maximum load for the mule; this was not done, however.

The implications of a heavy load on a mule operating in mountainous terrain are numerous. The load placed on the mule’s joints in the descents (Figure 14) are likely to be significant and will have contributed to the tendon sheath effusions in this mule. The load will press on the underlying burdâa, transmitting pressure to the weight bearing parts of the mule’s back. The precise dimensions of the weight bearing surface area will vary with the mule’s conformation; this can be evaluated for any given mule by considering the sweaty impression created by the burdâa after a few hour’s work (Figure 15). This surface should be as large as possible to ensure that the blood supply to the underlying tissues is not inhibited. Brager [8] asserts that this pressure should not exceed 80g/cm2.

A number of factors and questions need to be considered when answering this question:

The viewpoints of each team member will differ according to the member’s conditioning, biases, priorities and understanding of wound healing. These differences can be very pronounced and should not be overlooked. The wounds cannot be reduced to a simple clinical problem and managed in isolation. This may appear counter-intuitive to many clinicians whose instinct would often be to consider the wound management plan as a clinical issue that requires a well reasoned clinical solution to be formulated, in accordance with evidence-based, or at least science-based, medicine. Such a view point reflects the clinician’s often exaggerated fear of complications and bias in favour of treatment as well as their failure or inability to take into account the complex realities of a field (real-life) situation.

The owner, by contrast, is likely to view such wounds as common place and of little significance. Such wounds usually heal by themselves and do not seem to affect the mule’s ability to work. If the wounds have never been taken seriously and treated before, why change? This difference in opinion was clearly demonstrated by the muleteer’s behaviour on the final day of the expedition. Whereas the author considered the mule to be “cassé”, that is to say broken, the muleteer did not think so and certainly did want his friends and family to think that the mule was “broken”. He clearly feared losing face in the eyes of his wife, family and friends.

In deciding whether to treat the mule’s wounds the pros and cons of an intervention need to be weighed up:

In this case, the clipping and cleaning of the wounds allowed an evaluation of the wound to be made. This can often help identify factors that need to be addressed and eliminated if wound healing is to progress. Pieces of nylon rope often break off within the tissues and can create chronic foreign body reactions (Boubker, personal communication). The laying bare of the wound allowed the owner and guide to see clearly the extent of the wound, its circumferential nature and the fact that it had been caused by a tether rather than by stones, as the owner had thought. This allowed the cause to be addressed more forcefully and, it is hoped, convinced the owner of the need to use a better designed tethering system.

The cleaning of the wound identified a plug of necrotic tissue that needed to be eliminated in order to allow wound healing to progress. This cleaning and debridement  produced fresh wounds that required protection from contamination and infection. This was not easily undertaken in a laden pack mule, covering some 20km or more a day, in dusty conditions.

Dressings are often used to cover wounds to the lower limbs of equines in order to protect them from contamination and oedema, absorb exudates, minimise movement and protect against further trauma [12][13]. Bandages also have the ability to affect moisture, temperature, pH and gaseous exchange at the wound site [12][13]. A wide range of factors have been identified as having the ability to slow or prevent wound healing. These include infection, inflammation, poor oxygenation, contamination, foreign bodies, movement, recurrent trauma and desiccation. Wound management plans seek to eliminate these factors and bandages are generally resorted to in order to achieve these objectives.

Dressings have, however, been shown to lead to greater wound retraction and the promotion of excessive granulation tissue in surgical models of second intention wound healing in the distal limb of horses [14]. This study concluded that unbandaged wounds did not take any longer to heal and showed greater contraction initially, suggesting that the benefits of bandaging wounds on the lower limbs of horses are, as yet, unproven, and  may even be harmful where it promotes the formation of excess granulation tissue. It should be noted, however, that the effect of bandaging remains unclear because of the differences in the design and objectives of the various studies of wound healing conducted to date [14].

Dressings and bandages are costly and require a certain amount of knowledge and training if they are to be used correctly. In undeveloped countries, the availability of dressings is often limited and the owner is unlikely to be inclined or able to continue dressing wounds themselves.

In this case study, it is unclear what benefit arose from the use of the dressings during the course of the expedition. The wounds to the dorsal aspect of the pastern had healed by the time the dressing was removed on day 4 but, it could also be argued that they would probably have healed by themselves. The removal of the plug of necrotic tissue on day 4 created a wound that, following the owner's removal of the dressing and refusal to dress the wound, was left undressed to heal by secondary intention.

This is a difficult question to answer for it requires us to consider whether the decision to treat was sensible given the fact that ongoing care could not be guaranteed. Any attempt to answer this question must seek to quantify the risks and evaluate that which is to be gained by treatment, whilst at the same time attempting to evaluate that which may be gained by not treating.

The risks associated with an open tethering wound to the pastern of a working equine are difficult to quantify. Bacterial contamination of the wound is to be expected but it is difficult to predict how often it will overwhelm the animal’s ability to deal with it. It is known that ponies mount a more effective acute inflammation during second intention wound healing than horses [15][16]. It is likely that this is also true of mules, given their reputed resistance to disease. The ability to rapidly mobilise large numbers of polymorphonuclear leucocytes may allow wound infection to be controlled and the wound to pass swiftly from the inflammatory phase to the granulation phase. Tetanus is often cited as a serious consequence of tethering injuries [17] but there has been little work conducted to quantify this risk relative to the thousands of mules with pastern wounds. During an eighteen month period between 2003 and 2004, the Society for the Protection of Animals Abroad (SPANA) hospitalised 56 cases of equine tetanus in Morocco [17]. It is unclear whether this figure reflects a widespread resistance to the disease amongst working equines in Morocco and, without further research, it is impossible to draw any conclusions. With regard to the treatment of such wounds one is left wondering whether anti-tetanus prophylaxis and wound dressings are indicated.

In this case example, it is quite possible that the wound’s healing may have been set back by the author’s interventions, especially as the wound treatment only lasted a short period of time and was not completed. It is also possible that the muleteer may have been upset and alienated by the author’s attempts to treat his mule’s wounds. The lessons drawn and retained by the muleteer from these experiences may thus have been miseducative. Clearly these criticisms are speculative but it is important that any intervention be reviewed in order to seek to identify any undesirable results and ultimately inform and improve practice.

Where treatments fail to promote sustainable solutions, they can promote a dependency on solutions that cannot realistically be provided locally. The use of dressings can therefore promote a reliance on foreign visitors and deflect from efforts to address the underlying problem. It can therefore be argued that energies may be best expended in eliminating the cause and changing husbandry practices.

In evaluating the wound and deciding on its management, the Mountain Guide is constrained by circumstance and confronted by tradition. He will need to consider the various factors that are likely to have provoked the wound as well as those that prevent it from healing (Table 1). Where possible and practical, the Guide should act wisely to ensure that the mule’s welfare is respected.

|

Factors that can predispose to tethering injuries and harness sores

Factors that can prevent wound healing:

|

The Mountain Guide, or Expedition Leader, working with pack animals on expedition will often find themselves confronted with tethering injuries and saddle sores. These are always best prevented; the Mountain Guide should therefore be able to identify any mule that is unfit for work as well as those tethers and saddle blankets that are likely to cause injury to the pack animal on expedition. Where wounds requiring treatment are identified during the expedition, a wound management plan will need to be established that addresses the underlying cause and manages those factors that prevent wound healing.

The owner of the pack animal will have their own views on the way their property should be managed and treated. These can conflict with the Expedition Leader’s and clients views on best practice. The attitudes, knowledge and beliefs of the owner need to be considered and understood if the Expedition Leader is to change the owner’s behaviour and ensure that the causes of harness related injuries are eliminated. This is no easy task and is an excellent example of the importance of socio-cultural factors and good communication in wound management.

This case study has described the author’s experiences, the need to reflect in and on practice and the re-ordering of priorities that has flowed from this process of reflection.

The author would like to express his gratitude to the Donkey Sanctuary and Stephen Blakeway MRCVS for supporting and encouraging the author's work on the responsibilities of mountain guides and expedition leaders to pack animals on expedition. The author would also like to thank the staff of SPANA UK and SPANA Maroc for all the help, advice and assistance they have provided and their continued commitment to improving the welfare of expedition mules.

1. Daly H.W. Manual of pack transportation. Geneva: The Long Rider’s Guild Press, 2001 (Original work published 1910).

2. Guenon A. La Grande Histoire du Mulet. 1899.

3. Hauer J. The natural superiority of mules. Guildford, Connecticut: Lyons, 2006.

4. Williams J.O, Speelman S.R. Mule production. Washington: United States Department of Agriculture, 1948.

5. Milhaud C, Coll J.L. Utilisation du mulet dans l’Armée Française. Bull. Soc. Fr. Hist. Med. Sci. Vet 2004; 3(1): 60-69.

6. Field Manual No 3-05.213 special forces use of pack animals. Washington DC, USA Headquarters, Department of the Army: United States Army, 2004.

7. Cousquer G.O. Ethical responsibilities to pack animals on expedition: Design and development of a curriculum for the Moroccan Mountain Guide. MSc Dissertation. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 2009.

8. Brager E. Techniques du voyage ŕ cheval. Paris: Nathan, 2005.

9. Pearson R.A, Simalenga E, Krecek R. Harnessing and hitching donkeys, horses and mules for work. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, 2003.

10. Hadrill D. Horse healthcare. A manual for animal health workers and owners. London: ITDG Publishing, 2002.

11. Geus, V. Maroc: Treks, randonnés, balades, culture, nature. Grenoble, France: Editions de la Boussole, 2007.

12. Knottenbelt D.C. Basic wound management. In: Knottenbelt D.C, editor. Handbook of equine wound management. London: Saunders, 2003; 39-77.

13. Gomez J.H, Hanson R.R. Use of bandages in equine wound management. Vet Clin North Am 2005; 21: 91-104.

14. Dart A.J, Hawkins N.R, Dart C.M, Jeffcott L.B, Canfield P. Effect of bandaging on second intention healing of wounds of the distal limb in horses. Aust Vet J 2009; 87(6): 215-128.

15. Wilmink J.M, Stolk P.W, Van Weeren P.R, Barneveld A. Differences in second-intention wound healing between horses and ponies: macroscopic aspects. Equine Vet. J 1999a; 31: 53-60.

16. Wilmink J.M, Van Weeren P.R, Stolk P.W, Van Mil F.N, Barneveld A. Differences in second-intention wound healing between horses and ponies: histological aspects. Equine Vet. J 1999b; 31: 61-67.

17. Kay G. How useful is tetanus antitoxin in the treatment of equidae with tetanus? A comparison of three treatment protocols used in the management of 56 cases of equine tetanus presented to the SPANA clinics in Morocco in 2003/2004. In: Pearson R.A, editor. The fifth international colloquium on working equines: The future for working equines; 2007; Donkey Sactuary, Sidmouth.